This Old Tree

Old trees are awe inspiring links to the past that fire our imagination. What are their stories? Seasoned arborist and amateur historian Doug Still interviews local experts, historians, and regular folks to celebrate the myths and uncover the real tales. If you're a tree lover, join in to look "beyond the plaque" at heritage trees and the human stories behind them. Monthly.

This Old Tree

Harlem's Tree of Hope

Use Left/Right to seek, Home/End to jump to start or end. Hold shift to jump forward or backward.

Picture yourself in Harlem in New York City, and it’s the 1920’s. There’s a cultural awakening going on - there’s jazz and dance, theater and literature, big celebrities and lots of new talent looking for a break. And of course - because this is a show about trees - there's a tree that becomes a symbol of the Harlem Renaissance. It’s the Tree of Hope, and it was a good luck charm to black performers looking to make the big time. Garden historian and storyteller Abra Lee tells the story of this particular tree’s rise to fame, its demise, and its enduring legacy.

Guest

Abra Lee

Garden Historian, Horticulturist, Arborist

Author of the forthcoming book, Conquer the Soil: Black America and the Untold Story of Our Country's Gardeners, Farmers, and Growers (2025)

conquerthesoil.com

Consulting Editor

David Still, II

Theme Music

"This Old Tree," Diccon Lee, www.deeleetree.com

Artwork

Dahn Hiuni, www.dahnhiuni.com/home

Website

thisoldtree.show

Transcripts available.

Follow on

Facebook or Instagram

This Old Tree podcast is a sponsored project of the New England Chapter of the International Society of Arboriculture. To support This Old Tree and New England ISA, click here.

We want to hear about the favorite tree in your life! To submit a ~4 or 5 minute audio story for consideration for an upcoming episode of "Tree Story Shorts" on This Old Tree, record the story on your phone’s voice memo app and email to:

doug@thisoldtree.net

This episode was written in part at LitArts RI, a community organization and co-working space that supports Rhode Island's creators.

litartsri.org

EP 8 - HARLEM'S TREE OF HOPE

Doug Still: Picture this. We're in Harlem in New York City, and it's the 1920's.

[music]

There's a cultural awakening going on. There’s jazz and dance, theatre and literature, big celebrities and lots of new talent looking for a break. And of course, because this is a show about trees, there is a tree that somehow fits into all of this, a symbol of the Harlem Renaissance. It’s the Tree of Hope, and it was a good luck charm to black performers looking to make the big time. Garden historian and storyteller, Abra Lee, is here to tell the story of this particular tree's rise to fame, its demise, and its enduring legacy. That's all coming up. I'm Doug Still, and welcome to This Old Tree.

[This Old Tree Podcast theme]

Doug Still: A long time ago, a mature elm tree stood on the East side of 7th Avenue between 131st and 132nd Streets in New York City, although 7th Avenue is now known as Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Boulevard. It was an American elm tree, that is clear to me from photos of the 1920s, but it is long gone.

[traffic sounds]

Doug Still: Gone, too, is any trace of the Roaring 20s. Go to the spot now, and you'll see a sleek new apartment building that spans the entire block. Clean, modern, and bland. There are three new little leaf linden trees planted there, hoping to thrive, but otherwise there's not much to draw your eye. The Williams Institutional Christian Methodist Episcopal Church occupies one of the double doors, hardly noticeable, but a presence since the 1950s.

But take a time machine back 100 years, and this block was Thriving with a capital T. This was along the Boulevard of Dreams, full of nightclubs and theatres, and dance halls. 7th Avenue and 131st Street was known to some as The Corner, with Connie's Inn and other clubs. Another one nearby was the Hoofers Club, a hangout for top jazz performers and tap dancers. And the biggest and most famous venue of the day was the Lafayette Theatre, with its huge marquee lighting up the night and renowned productions that brought in droves of people from all over the city. Our Tree of Hope stood next to the Lafayette Theatre and is most associated with it, as we'll find out later.

[music]

It was the height of the Harlem Renaissance, which was, as Professor Cheryl Wall put it, a time when black people redefined themselves and announced themselves into modernity. It was an intellectual and cultural awakening that found its center in Harlem but stretched to other cities around the country like Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia, and Washington, D. C., and also to Paris, Berlin, and London. The backdrop was the Great Migration, which was the mass movement of southern rural blacks to northern cities to seek better wages and living conditions and to escape life-threatening mob violence. It was a fresh start in a time of great optimism and the artistic legacy, jazz, dance, fashion, literature, and drama, was a gift to the world.

But back to our block on 7th Avenue, what was the Tree of Hope and what did it have to do with all of this? I'd like to introduce you to my new friend, Abra Lee. Abra is a garden historian, storyteller horticulturist, and former city parks arborist based in Georgia. Her degree in ornamental horticulture is from Auburn University, and she's also an alumna of the prestigious Longwood Gardens Fellows Program, which she completed in 2020. Recently, Abra has worked as a freelance horticultural writer and lecturer. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Fine Gardening, Veranda Magazine, and NPR. Her first book, Conquer the Soil: Black America and the Untold Stories of Our Country's Gardeners, Farmers, and Growers is due out in 2025. Her work seeks to tell love stories about the folklore, history, and art of horticulture. Abra, welcome to the show.

Abra Lee: Thank you, Doug. I am happy to be here with you today. Happy 2023. It is so early in the year. First week of the year.

Doug Still: Yes. Happy New Year to you too. And I think that I told you in one of our previous conversations that I was also-- Well, I also applied to the Longwood Fellows Program at Longwood Garden way back when. [laughs]

Abra Lee: Oh, wow.

Dougl Still: The early 90s.

Abra Lee: Yeah.

Doug Still: I went through a grueling three-day interview process, and I did not get in. So, congratulations to you. [laughs]

Abra Lee: Thank you. And I will say the process still feels grueling. What's interesting about that is that it may be self-formed by us, the interviewees, because the people at Longwood are wonderful, but it feels intense when you're up there. It really does.

Doug Still: Yeah. And Longwood Gardens is so beautiful. It's in the Brandywine Valley in southeastern Pennsylvania. But we're here to talk about the Tree of Hope at your suggestion. I was wondering if you could set the scene for this story. Where was it located and how did the story first come about?

Abra Lee: The Tree of Hope was located on 7th Avenue and 131st Street in Harlem. And some people would say 7th Avenue and 132nd Street in Harlem. It is a tree that people gathered under. When I say people, I mean specifically the black community in Harlem. So, at the prime of the Tree of Hope, it is the Roaring 20s, the Harlem Renaissance is happening, black businesses are thriving, black communities are thriving. This is in the era of the early 1900. The post-Reconstruction era of America had occurred in early 1900s and black people, black communities, many had migrated from the south to the north. So, they're going to New York, places like Harlem, in hopes of seeking a better life.

Doug Still: Yeah. I know that it could fill an entire course or encyclopedia about what the Harlem Renaissance was about and everything that happened. But how would you describe it? How is it important to American culture?

Abra Lee: Renaissance was the part or maybe certainly the first time in America where the illumination of black art, black culture, black literature is "mainstream." It is validated by people outside of the black community as black culture in America being something hyper specific and special to itself. So, these people who are descendants of the formerly enslaved have not only come to America, their ancestors, through way of bondage, they have been stripped of everything they knew throughout the diaspora and recreated their own sound, their own style, their own music, their own art, their own way of acting. Jazz is verbed from this. So, that is what the Harlem Renaissance means. It puts, honestly, America on the map as an artistic contributor to the globe is what it does.

Doug Still: Right. And as you were saying, people were migrating from the south to the north and had this area of New York City that became their own.

Abra Lee: Yes.

Doug Still: There was this flowering of theatre in writing and music.

Abra Lee: And ideas in community and fashion and business and economics. The Tree of Hope didn't start off being called the Tree of Hope. This is where it gets fun. The Tree of Hope is like any other legend. It's bigger than itself, and it has many iterations and many names. Some people, the old timers, a Harlem native or necessarily, maybe not necessarily a native, but a person who is a part of the Harlem community, they call them Harlemites, many of them said that the Tree of Hope started off being called the Tree of Wisdom or the Tree of Knowledge. It was no different than when you saw people gather in these open-air spaces outside of Europe and have their symposiums and discuss the economy, discuss politics, discuss gossip. And with that, people were able to exchange messages.

It was the message board, it was the internet, it was the chatroom, it was the everything for Harlem.

Doug Still: What in particular went on this block on 7th Avenue between 131st and 132nd Street? What was it known for?

Abra Lee: It was known most famously for the Lafayette Theatre being diagonal to that tree. The Lafayette Theatre was Black Hollywood at the time. It is where the successful performers were doing their acts and their stage shows, whether it was comedy, whether it was music, whether it was theatrical. Or it was a place where hopeful actors who were seeking to be the next person of fame and fortune would stand in front of this tree. What was so significant is that if you were a Broadway manager or a producer, you could walk right outside of that theatre and in a moment's notice, grab whatever type of performer that you needed to fill in at the Lafayette Theatre. And that is when it starts becoming the Tree of Hope.

I do want to tell you a name that is credited to naming it the Tree of Hope. Of course, there's many iterations. I can't validate this. But the person credited to naming the Tree of Hope, is a person named Lee Whipper. Lee Whipper, I don't know much about their story, but the legend goes that there were some performers who were unable to get paid for their work, and they were gathering under this tree just like anyone else, stage performers.

Doug Still: It was probably hot, it was probably summer.

Abra Lee: Of course.

Doug Still: I'm looking at the old photos, and it's the only [chuckles] tree on the block that I can see.

Abra Lee: It's the only tree.

Doug Still: So, naturally, they would be underneath the tree.

Abra Lee: They would be underneath the tree. What they did is that one of them rub the tree and pretty much prayed that they would get their money, they would get paid for the work they had done. They had done the work, but they hadn't gotten paid. And lo and behold, a few days later, they got their money. And so, word gets out that this tree has magical powers. They said that people have more faith in that tree than they even had in themselves. And that is when it becomes the Tree of Hope. And you're right, there weren't other trees on that street to gather under. It was truly a gathering spot.

Douglas Still: So, what I read was that it wasn't just during the day, but people gathered underneath the tree all night long. It was like a meeting place. Probably, performances were going on even afterwards at the Lafayette Theatre and people were there on into the night.

Abra Lee: Yes. They said that the talk was fast and free up under that tree. [crosstalk] The conversation was fast and free. If you were a gossip columnist, you could get more information from a two-minute conversation under that tree than you could get from a three-column written out of the paper. So, that is what the Tree of Hope was. We're not talking about 10 people, 15 people, 20. We're talking about hundreds, even thousands of people at a time gathered under the street. It sounds like, "Oh, Abra, you're telling us tall tales." Well, guess what, y'all? There are pictures that validate this and show thousands of people on the block lingering, socializing, and meeting, having community, having church up under The Tree of Hope. And so, it was a friend of the community, it was a neighbor, it was everything to Harlem.

[music]

Doug Still: Next up, I talked more with Abra Lee about the performance venues on the block, some of the famous performers there, and the eventual loss of the Tree of Hope, and what happened. You're listening to This Old Tree.

So, I'm looking at one of or I looked at one of the old photos, and the tree wasn't actually directly in front of the Lafayette Theatre. It was right next door. And the establishment, there was Connie's Inn.

Abra Lee: Yes.

Doug Still: Have you heard of Connie's Inn, or do you know what Connie's Inn was?

Abra Lee: Yes, I have Connie's name. The last name is a B. I believe he's a gentleman. And Connie owned it in there. And this was also a person who was a mover and shaker. I think they even call Connie a wheeler and dealer from Harlem.

Doug Still: I looked it up. This was prohibition and Connie's Inn was a speakeasy. It was established by Connie Immerman and his brothers who emigrated from Latvia. It was a nightclub in the basement that featured acts like Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller, Wilbur Sweatman, and Fletcher Henderson. Like the Cotton Club over on 142nd street, the audience was for whites only. In 1934, it vacated and moved downtown, and the Ubangi Club moved into the spot. The Ubangi Club featured black, cross-dressing, gay, and lesbian performers like Gladys Bentley. There was a lot going on. At Lafayette Theatre, there was Connie's Inn, there's another one called The Hoofers Club. So, all of these establishments had performers, and people would meet under this tree, and probably take jobs in different places.

Abra Lee: Yes, absolutely. This is the thing. People would go there to seek a job. But people who had a job, the performers who were successful and already employed in theatre knew to pay their respects to that tree. So, where they may not kiss the tree or pray to it, they would certainly touch the tree. This was a tree that people felt superstition about. They really felt that you are going to pay homage to this tree if you want your success to continue. I'm saying that because there was a spiritual connection to this tree in the community. If we think back of the people that are under this tree, that community has built the ancestors that would coincide with their beliefs about nature and the power that it does have. So, it was beyond important. It was family. It was family.

Doug Still: Its fame was most intertwined with the Lafayette Theatre. If the Harlem Renaissance mainstreamed the illumination of black culture, as Abra explained, the Lafayette was an early beacon. It was the first major theatre to desegregate in 1913 allowing African American theatre goers to sit in the orchestra alongside their white counterparts. The Lafayette staged Broadway hits such as Madame X, and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. The musical revue that became known as Darktown Follies popularized two dances, Ballin' the Jack and also the Texas Tommy, which grew into the Lindy Hop. Duke Ellington made his New York debut here. The Lafayette players were the resident stock company, and they performed new plays in classics before almost exclusively African American audiences.

Abra Lee: The Lafayette Theatre was known for having the biggest, greatest performers of the day. So, people like the great singer and orator, Paul Robeson, people like Ethel Waters, the famous entertainer, tap dancer, performer, people like Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, who was considered or is considered the greatest tap dancer ever. This is what the Lafayette Theatre produced. And these are names that you and I may recognize today from days of old. There are names beyond their names that may not ring a bell today better, even more legendary to those people. The Lafayette Theatre was Hollywood. It was Hollywood for the black community. It was where you went to change your life, to change your generational wealth. To change your economic status, it was that important.

Doug Still: My understanding is, it was a combination of shows from Broadway from downtown, but it was also original shows or plays written by African American playwrights and writers as well.

Abra Lee: It was. It was a Black Broadway. It wasn't just Broadway shows, it was comedy shows, it was opera shows, it was theatrical shows. Any type of show that you-- I think you just said vaudeville, that you can relate to entertainment. That is what happened at the Lafayette Theatre. It was something that was known coast to coast in the black community. You got to think this is a time in Harlem where Langston Hughes is roaming the streets. Zora Neale Hurston, the incredible writer, a great friend of Langston Hughes, is roaming the streets. Countee Cullen, Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, I mean, the names go on and on. This is when The Tree of Hope is at its prime. So, every name that you can think about, Louis Armstrong, Josephine Baker, that is what is attached to this tree.

Doug Still: One name that you mentioned was Ethel Waters. Could you tell me about Ethel Waters and who she was?

Abra Lee: Ethel Waters was of her time-- and I am no entertainment historian, but I certainly do know a little bit about her career. If you think of the most famous black Hollywood actresses now, people like-- Think of Octavia Spencer, because I'm Auburn graduate. You think of other black actresses who have succeeded. I don't know why my mind is blanking, y'all. I'm a horticulturist and I'm sitting here thinking, "I can see a hundred black actresses in front of my face and I'm naming none."

Doug Still: They were the celebrities of the time.

Abra Lee: Yes, they were the celebrities of the time. That is what Ethel Waters was. She had the fame, she had the fortune, she had the following, she had the gossip callers following her, the paparazzi, all of that. That is what Ethel Waters was. She was one of the most famous people in America.

[Ethel Waters singing]

Doug Still: So, this was before the Apollo Theater.

Abra Lee: Right. The Lafayette Theatre precedes the Apollo Theater. What happens is the 1930s come along, and what we know is that is when the Great Depression starts. At the end of the 1920s, and people really were holding out hope that things would turn around, things would change, but unfortunately, that was not the case. The felling, when the Tree of Hope is removed-

Doug Still: This was 1934.

Abra Lee: -it is considered the beginning of the end of that era in Harlem. And people said, "Harlem was never the same."

Doug Still: Now, I understand that the Tree of Hope was removed, because they did a street widening project. The city came in and widened 7th Avenue and had to remove the tree. And so, it was the automobile. This happened everywhere. This happened all throughout New York City. I'm in Providence now. There's one major boulevard called Elmwood Avenue that had a double [unintelligible 00:20:26] of American elm trees. And in the 1930s, to make room for commuters to drive in and out of the downtown, they widen the street and removed-- There was a big outcry. It was in the newspaper. So, this is not unusual. With the automobile, we lost a lot of tree canopy, unfortunately.

Abra Lee: The way that it was reported in the Harlem papers and in the black newspapers around the country, because this was national news in our community was that this was the crash heard around the world. It wasn't a stock market crash. It was this tree crash into the ground.

Doug Still: [laughs]

Abra Lee: The reporters stated that cars had become more important than pedestrians. And so, the city came in, and cut down this tree, and people could not believe what was happening. They said that there was much weeping, there was much wailing, and if you've ever been to a good old-fashioned funeral at a black church or a Baptist church or a country church, you know what that's about. There were trumpeters who brought out their trumpets and started playing the St. Louis Blues-

Doug Still: Wow.

Abra Lee: -in a slow sound. So, there was a real-- [crosstalk]

Doug Still: It's very upsetting.

Abra Lee: Oh, my gosh, yes. So upsetting to the point when the Parks Department came through that the people who were witnessing this-- A crowd starts to gather. There's already hundreds of people there daily, but more and more people gather, and someone has the wherewithal to say, "Let me go get my saw, let me go get my axe, let me go get my hatchet, and I am going to start cutting up pieces of the tree." And they started selling the pieces of the tree on the spot.

Doug Still: Right. They kept it and they handed it out, and some people sold it. I don't know how they were able to sell it.

Abra Lee: It's the Tree of Hope and I got the saw. Doug, you don't have a saw and you want this big chunk, you can't just walk off with it for free. How are you going to get it to your house? And it is the 1930s. There's hustle in there too now. These are business folks.

Doug Still: Right.

Abra Lee: So, yes. There were people who bought portions of the tree. There were people who grabbed portions of the tree. They say, "Look, if you didn't have any money, you were picking up the sawdust off the street and putting it in your pocket for this tree." People were taking roots off of this tree and that was how important it was to them. And it was so important that once the tree was completely failed and gone, there were people in Harlem that avoided that area altogether moving forward. They didn't want any parts of it, because they believed it to be a bad omen when that tree was removed.

Doug Still: Here's the title from a New York times article about it from August 21st, 1934. WISHING TREE'S END SADDENS HARLEM; ' Charmed Circle' Where Noted Stage Folk Prayed for Jobs Is Bereft of Fetish. WOOD CUT FOR SOUVENIRS 400 Watch in Gloom as Source of Old Superstition Falls in Widening of 7th Avenue. Abra then brought out an article of her own from her files.

Abra Lee: It's so interesting. I love these headlines. I don't know if you've seen this one. It says, "It was murder, Jack. " People were serious about it. That was a first-person account of the tree being felled.

Doug Still: Oh, wow.

Abra Lee: You can see the people sawing. I don't know if you can see that. You can see the folks sawing the tree up.

Doug Still: Wow.

Abra Lee: You can see, "It was murder, Jack-"

Doug Still: Where did you find that?

Abra Lee: So, that's the thing. You mentioned it was written in the New York Times. This was in the Amsterdam News, which was a black paper. The Times was the Times, but this was the news to them.

Doug Still: So, pieces of the tree are being sold, taken away as souvenirs. I'd like to get to one in particular. There was a piece of that tree taken by or purchased by, perhaps, Ralph Cooper, Sr.

Abra Lee: That's correct. And knowing his influence, knowing who he was and his relationship as an entertainer, as a famed person of that community.

Doug Still: Well, who was Ralph Cooper, Sr.?

Abra Lee: Ralph Cooper was a performer. He was an MC. He was a man about town. He was a very handsome black man. He was the Clark Gable. Gone with the Wind was popular at the time, and he was considered dark Gable, which I think is hilarious, because he's a black guy. He's just this dashing, charming, beloved member of the entertainment community. And knowing who he was, his relationship to the Lafayette Theatre, being a performer there, having a great business relationship, I highly doubt he paid for his hunk of the tree. But the way legend has it is that he had a portion of this tree when the tree was cut and had a stage hand mounted stage left at the Apollo theater.

Doug Still: So, the Apollo just opened.

Abra Lee: Yes.

Doug Still: The Apollo Theater on 125th Street had actually opened in the early 1920s, but it became a venue for black performers and patrons in 1934, becoming more like what we know it is today.

Abra Lee: But the Apollo had been known for its amateur nights. When you're at the Lafayette and you're a professional at this point or you're trying to become a famous professional, Apollo is amateur night and that is what it is known for, even to this day. They still have some amateur nights at the Apollo. Maybe not like the Heyday, but they're still there. And Ralph Cooper was the MC, ABC, which was a new broadcasting company in America at the time had gone to the Apollo in November of 1934 to live broadcast nationally, the amateur night. And on that night, Ralph Cooper, and perhaps before, maybe not specifically on that night, he had someone mount a portion of the Tree of Hope on the stage. And the intent was that you needed touch this tree. This tree was a part of the community, and you needed it to hope that you weren't going to get booed off the stage. Because at the Apollo during the amateur night, your success and your failure is judged by the audience. They have a gentleman called the Sandman that would come out with a hook and pull you off the stage if you were booed.

Doug Still: [laughs]

Abra Lee: At one point, they would shoot you off the stage. Not literal bullets, but blanks, and the audience would react to that, these blank guns, and they go pow, pow, pow, and shoot you off. But if you weren't booed off the stage and the audience was roaring and excited about you, it could change your life and that was what Ralph Cooper brought. He brought the national fame and national attention through radio, honestly, what we're doing now, and that is what I feel like illuminated the Tree of Hope into infamy, to be honest.

Doug Still: So, he took a slice of that tree. It was about a foot tall and about 18 inches in diameter, and he had a stagehand take it, shellac it, and apparently put it on a gold pedestal.

Abra Lee: That's right. And mount it. That's right.

Doug Still: It's right on stage.

Abra Lee: To this day.

Doug Still: It's been on stage until this day.

Abra Lee: Since 1934, it has been on that stage. It has. If anyone who goes on the stage of the Apollo-- I can tell you, I have watched many an amateur night showtime at the Apollo when I was growing up. If you walk past the stump and don't touch it, they won't even let you walk up to the mic without touching that tree stump.

Doug Still: Yeah. You can't let them go on without touching the Tree of Hope.

Abra Lee: No. And if you don't, you honestly start off on the wrong foot, the audience. You really do. So, it is that important. I mean, we're talking almost 100 years now.

Doug Still: So, does every performer touch the Tree of Hope before they go on stage, obviously, an amateur night, but the professionals too with Stevie Wonder--?

[crosstalk]

Abra Lee: Absolutely. Gladys Knight, Beyoncé. There's not a professional black performer, entertainer who has performed at the Apollo, no matter how great Michael Jackson brand you are, you have touched that tree. I don't think we know their name anymore.

Doug Still: So, the Tree of Hope, when it was on 7th Avenue, it was along the curb and it got removed, but the stump of it was moved to the median, the new median, and there was a plaque. Bill "Bojangles" Robinson was responsible for doing that. And he got the mayor. Mayor La Guardia came out and they were a big ceremony. Could you tell me who Bill Robinson was?

Abra Lee: Yes. Bill Robinson was probably the most famous living performer. We just said our name today is Beyoncé. And in his day, he was that. He was the most famous performer there, not just in the black community, famous worldwide.

Bill Robinson: [singing] Make 'em play that crazy thing again I've got to do that lazy swing again Hi-ho, doin' the new lowdown! Got my feet to misbehaving now Got a soul that's not for saving now Hi-ho, doin' the new lowdown!

Abra Lee: This was a person who had the respect of the Rockefellers, Fiorello-- If I'm saying is incorrect, Mayor La Guardia. So, when the tree was removed and there is an obituary in the paper and there are poems written, and as I said, there is a whole procession to mourn this tree. People are wiring in their condolences. Bill Robinson goes to City Hall, he goes to the mayor and says, "Long story short, what have you done here? You have destroyed this community. And guess what? You got an election in November, don't you?"

So, it was no coincidence that two days before the November election, Mayor Fiorello, Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, who wasn't just only one of the most famous entertainment world, he's also considered the Mayor of Harlem, the Commissioner of the Park Department that cut the tree down, shows up other mayors of other boroughs, or people who are considered "mayors" show up on that day, and a big hunk of that tree is replanted in the middle of the median, the island in that street.

Doug Still: From what I can tell, there was a piece of the stump and then there's also a new tree planted, a new Tree of Hope.

Abra Lee: There was a new Tree plant of Hope, and then it was replanted in another location in 1941. So, what we're referencing now, you and I, is the Tree of Hope is brought down in late August of 1934. And two days before the November election of 1934, the New York election, the stump is replanted. It is a big deal. There's a beautiful picture that shows thousands, at least 3,000 people show up for this replanting of the stump. This is in the middle of the Great Depression. So, this is how important this tree is, and this is how powerful Bill "Bojangles" Robinson is that he is able to throw out the bat signal and say, "Y'all need to get y'all's tails down here and right this wrong that you have done in this community."

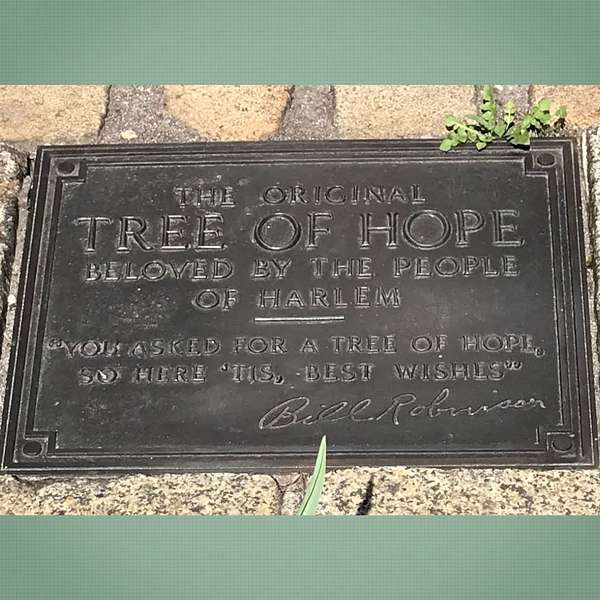

Doug Still: I'd like to read what it says on the plaque. So, the plaque says, "The original Tree of Hope beloved by the people of Harlem. "You asked for a Tree of Hope. So, here it is." Best wishes, Bill Robinson.

Abra Lee: To give context to your audience, Doug, the old timers at the time, the trees cut down people, and by people, I mean the reporters, the gossip columnists, the folks that lingered on the street and did their daily [unintelligible [00:32:03] to what they consider the old timers, the oldest people they could find in Harlem, the 100-year-olds and said, "Hey, how long has this tree been here? They could never settle on a day, but some people who were of a certain age of that time remembered that tree being there since 1875." So, we're talking 1934. So, they knew it had been there at least for 50 years at that point. So, that is the level of meaning that this tree had to the community where the old timers of white one. I was a child. It was there. So, it was so sad when it happened. It really was.

[music]

Doug Still: You are listening to This Old Tree. I've got more of garden historian, Abra Lee, who gets into the true meaning behind Harlem's Tree of Hope in just a minute.

The tree became a player in the arts folklore side of the Harlem Renaissance, which obviously was so much more. But are there works of art or literature since then that the tree itself has inspired?

Abra Lee: Yes, there was a Broadway play that was written about the tree. I think it was called the Wishing Tree. And I'm not saying that it was on major Broadway. It was probably on the black Broadway. Meaning, in Harlem that it was shown. And then, we get to the 1960s and the 1970s, this tree is still not forgotten. And there are artists that come along, like one of the fathers of Afrofuturism, Algernon Miller, to create a beautiful steel sculpture that is an abstract sculpture that honors the Tree of Hope and honors this legacy in Harlem, so that it is not forgotten to this day.

There was also a time, it was either the late 1960s or early 1970s, there was a ball that was in honor of Cab Callaway, and the person with the best costume would win this trip on Eastern Airlines. The airline is defunct now, but was the big deal of their time, the Delta of their time, the British Airways of their time. And the person came dressed as a Tree of Hope and had the pictures of Ethel Waters and of Cab Callaway and of Bill "Bojangles" Robinson attached to their outfit, and they won this top prize at that ball. They say legends never die. There's someone in Harlem today, ain't just someone, many someone that can tell you, if there's top five most famous things out of Harlem, this tree is the Harlem Renaissance. I mean, it is that important.

Doug Still: Why do you think a tree drew the attention of these performers and their fans as a repository for their particular hopes and dreams? It very well could have been a wall, or a stone, or a door handle or something, but why do they connect with this tree and why do you think a tree?

Abra Lee: The connection to the tree is certainly ancestral, it's communal. I think of trees of black people gathering under these mighty oak trees in the south that are along the river and having baptism. I think about people having full on church up under these trees. I think about the first reading of the Emancipation Proclamation stating that the Civil War was over, and that slavery was no longer legal in the United States happens under a tree. So, that is where community happens for many black people.

Tuskegee, one of the greatest universities in the United States, certainly the HBCU, historically black college and university, is built on a former plantation covered in trees at that time. So, I think about them almost like you think about the grand ceilings of these churches all across the world in Europe. That's what that canopy is to black people. And in these places where we can gather and feel free and be our unapologetic selves and speak in the language that we want to speak. The street flame, this is where we can create music. This is where we can exchange words and ideas. So, that is why that was important to that community. Honestly, I still would argue to this day.

Doug Still: It's funny. The theme of tree canopy acting like a cathedral or the roof of a cathedral is one that's found in other traditions as well. And we spoke about that in a previous podcast about the American elm and how it forms cathedral like canopies over streets. And so, it's interesting that you brought that up as having to do with this tree as well.

Abra Lee: Again, Harlem at this time, the Great Migration, where you see millions of black people leave the south, where the south is 90% black and half of the black south leaves and goes to Pittsburgh, and New York, and Chicago, and Dayton, Ohio seeking better lives. Even my own family members were part of this Great Migration. And I say that because this is a bunch of country boys and a bunch of country folk, men and women, country people that are really rolling around Harlem at the time. They're not necessarily mostly native New Yorkers. And so, they're used to hanging under trees in the south. I don't mean that in an insulting way in terms of lynching. I mean, gathering. I guess, the better word I should have used would have been gathering under trees in that southern heat, that humidity getting under the shade. So, it would have been a normal reaction for them to be a part of this tree.

The fact that this tree symbolized hope was parallel at the same time, since I brought up the word lynching and hanging from trees, in the south, oak tree and necessarily looked at as this great mighty thing or the great mighty elm, because it is used as domestic terrorism. So, there's just this really polar opposite thing of this tree, particularly in New York, representing hope and light and not death and destruction, the way that it would have represented possibly in certain parts of the south at the time.

Doug Still: Really, that's one of the legacies of the Harlem Renaissance is that black people have been able to reclaim their histories and stories and tell it for themselves.

Abra Lee: Absolutely. That was what the Harlem Renaissance was. You had the writer, someone who I certainly consider-- and not just me, many people consider her the star of the Harlem Renaissance in terms of writing, Zora Neale Hurston, where she unapologetically writes about the black community. She's not trying to be WB to boys and go to school in Germany. She's fine writing about the country black community in Florida, in her hometown, Eatonville, Florida. So, that is what the Harlem Renaissance is, where black people are saying, "We've got our own culture, we've got our own style, our own art, our own everything. We don't have to recreate what the Europeans, the Italians, even our own brothers and sisters in the continent of Africa are doing or in the Caribbean. We got our own thing here." And that was what was so special about the Harlem Renaissance.

Honestly, that's what's so special about the black community in America today. This is a community that was stripped of their culture, their language, their food, their parents, their relatives, their everything, their clothes. And then everything is taken from them, and then they recreate something completely new. That is how we have jazz, and hip hop, and Negro spirituals, and gospel music, and [unintelligible [00:39:17], and the list goes on and on, and the community is continuously reinventing itself.

Doug Still: Then with the interview about to wrap up, Abra dropped a big surprise about ancestor of hers.

Abra Lee: As we are talking about the Tree of Hope making its way to its forever home at the Apollo Theater outside of the pieces that were kept by the community, I have a fun fact Harlem story to tell. There is a woman, and your audience can look up her films on YouTube named Mabel Lee. Mabel Lee. And Mabel Lee is a relative of mine. She is someone that was raised as my grandfather's sister and made her way migrated from the south to north in New York. An incredible singer, dancer. She passed away in her 90s, not too long ago. When she passed away, her name was illuminated outside of the Apollo theater. And I was fortunate to meet her many times in my lifetime. She came down to, not only my grandfather's 90th birthday when my grandfather passed away. She was so important to our family and most importantly to my grandfather that we held off on his funeral to get Mabel Lee down here. So, she was truly an Apollo legend.

Doug Still: That's amazing. When did she perform?

Abra Lee: Oh, my gosh. From the 1930s, 1940s. And the Soundies, I almost want to compare them maybe to short films or music videos, but just a gorgeous, gorgeous woman. If you look up Mabel Lee and look up some of those films, there's a real famous one. I think it's called The Cat Can't Dance that she did, and she's singing and the trumpet players behind her. But that's my connection to the tree. You better believe, Mabel Lee, my relative-- Even though,

I haven't touched the Tree of Hope, I have a relative that has. And she's passed on as well, but she was truly a legend of Harlem and a legend of the Apollo. And honestly, God rest her soul, if she was here, I think you and I will be up there today getting a VIP tour of that tree.

Doug Still: Here in 2023, what inspires you about the Tree of Hope?

Abra Lee: What inspires me about the tree of hope is the possibility of what can happen tomorrow that as polarized as this country is. I would argue is an overused word, but really it's not. That is a very factual word. There is still hope, there is still a possibility, there is still a way. There is still a way to economic empowerment, there is still a way to exchange ideas that will better this country, better this world. The treat represents that, for lack of better words, that we really are the change that we want to see. It is possible, but it is only possible through human interaction and community and gathering that community again. So, I think if one word, the Tree of Hope represents to me, it is community and we must get back to that to build and to better and to succeed and thrive to survive.

Doug Still: Abra, I'm really enjoy talking with you today. I really appreciate you coming on the show and talking about the Tree of Hope and your thoughts about that.

Abra Lee: Thank you for having me, Doug. This has been so much fun, and I'm just appreciative to be with here today. It's a real honor. Thank you.

Doug Still: And I wish you a great 2023.

Abra Lee: I appreciate that. I think it's off to a great start. I accept the blessing, and I receive it, and I reciprocate that to you as well.

Doug Still: If heritage trees are living links to the past, in this case, it's a stump upon the Apollo stage. It's a good luck charm, but it's also a symbol of possibility and of community that every performer is invited to take part in. From Duke Ellington to Abra's great aunt, Mabel Lee, to the stars of today.

[The Cat Can't Dance plays]

Doug Still: You've been listening to This Old Tree, and I'm Doug Still. Again, I want to thank Abra Lee for being such a warm and entertaining guest. And I'd like to thank you, tree lovers, for joining us today. If you like the show, one way to show your support is to hit the subscribe button on your podcast app. And jeez, I'm going to get that Patreon link up on the show's webpage one of these days. I'll let you know. You can get links and information about Abra and the places we've talked about in the show notes and see photos and other related tree stuff, if you follow This Old Tree on Instagram, Facebook, and Mastodon.

Also, if you'd like to submit a three-minute tree story short about an important tree in your life, record it on the voice memo app on your phone and email it to me, I would love to hear from you. And you guessed it. This is Mabel Lee singing The Cat Can't Dance. Enjoy the rest of it and see you next time.

[The Cat Can't Dance plays]

[Transcript provided by SpeechDocs Podcast Transcription]

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.

Ologies with Alie Ward

Alie Ward

The Ancients

History Hit